On The Representational Horror of Film

- The Director by Daniel Kehlmann translated by Ross Benjamin

- Black Flame, by Gretchen Felker-Martin

Is not the reproduction of the illusion, in a certain sense also its correction?

– Gilles Deleuze, CINEMA I Movement-Image

I’ve started a new reading thread over on bluesky. It’s something I’ve done many times over the last few years and it’s always interesting to see the various serendipitous connections that reading can generate. Two of the very first books I read this year are both formally and stylistically divergent but find some interesting common ground in terms of their concern with the problem of film and how to translate and understand one set of representational technology (cinema) into another (language itself).

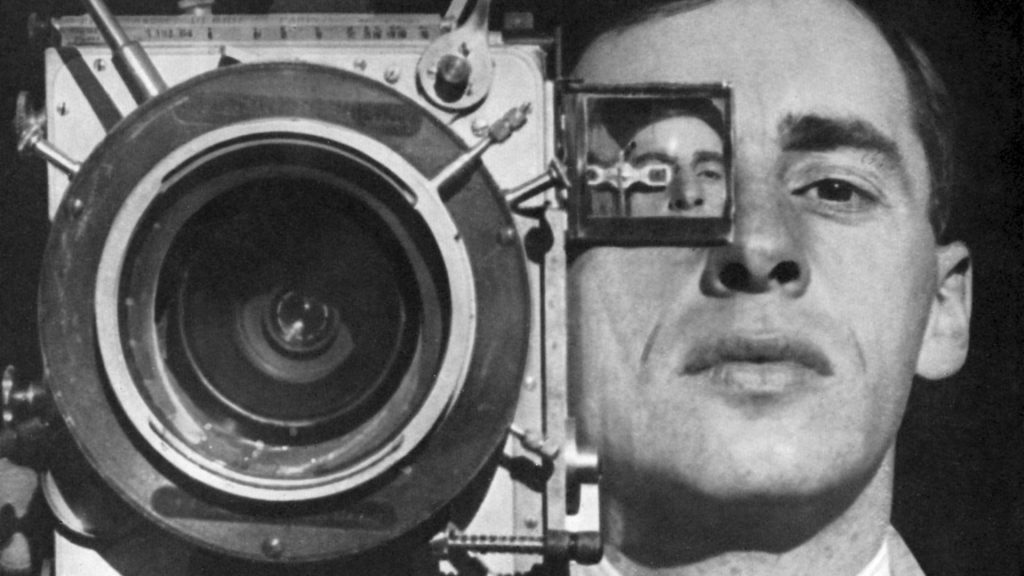

First, The Director by German writer Daniel Kehlmann. The novel follows a loosely fictionalized history of the film director G.W Pabst. Popular during the era of silent film, he was initially known as “Red Pabst” thanks to his interest in social realism and narratives concerning the lives of poor and working class women. As Blake Morrison points out in great review for the LRB, Pabst in 1934 was a committed, political filmaker: “Film must free itself from all ties to special interest groups and economic powers, from all forms of supervision – only then can it achieve its full potential. This liberation from outside influence will make film what … it was destined to be – the property of the masses!” Leaving Germany before the second World War he makes it to Hollywood, and is pressured into making a film that he thinks very little of and is certain will be a flop. When it is, and chafing against the lack of artistic freedom from the Hollywood studio system, he finds his way back to his native Austria and is suddenly unable to leave. There, he strikes a Faustian bargain with the new government and reluctantly agrees to start working on films again. Under the auspices of the government he made two films: The Comedians and Paracelsus as well as starting work on another film, The Molander Case, shot in Prague in 1944. The Red Army liberates the city and, with the film ready for editing, Pabst tries to smuggle the film out of the city and in the tumult, it’s lost, haunting Pabst who remains a shell of an artist for the rest of his career. There is an unspoken horror at the heart of the lost film, a moral, aesthetic and political nightmare that is suggested right at the beginning of the novel and won’t be fully revealed until the very concluding sections, underscoring exactly what Pabsts’s choices cost him.

Unlike Leni Riefenstahl, who also appears in the novel, Pabst was never a straightforward propagandist. He’s scathing about the loathsome Riefenstahl: “remember she can put you in a camp” he tells himself, watching her direct one of her movies on set, describing her as having skin cast from Bakelite. Yet it’s while he’s on set with her, Pabst realises she’s gathered gaunt faced extras from the Maxglan detention camp to flesh out the background scene. The novel is a great character study – a talented artist who idealizes their own potential aesthetic capability while allowing themselves to ignore the very material stuff that their art is dependent upon. There’s a moment where Pabst goes to the offices of the German government for a meeting with the Minister of Culture (clearly Goebbels but never identified as such). The Minister presses the script for The Comedians on him, reassuring Pabst that it’s “entirely a-political.” Pabst convinces himself that “all he had to do was make a hand gesture and say a few words.” The supremacy of art is Pabst’s refuge from the realities of the world but also an excuse for his own inability to reckon with the fact that film never exists in a vacuum — it is a social mechanism of image making and thus, inescapably put to social ends. The reveal of the apparent lost film at the end ramps up the bleak despair – so committed is Pabst to finishing his films by any means necessary he barely seems to register that many of his crew are being forcibly conscripted. Needing hundreds of people to fill out a crowd scene he pressurizes his assistant to find the hundreds of bodies necessary. Naturally, the people are found from a concentration camp, reified from bare life into nothing but a brief flickering background image.

The book itself is not just engrossed in the history of cinema but utilises its techniques too, particularly in its details of structure. Pabst was perhaps most widely admired for his skill as an editor – functioning as one of the pioneers of the craft. His use of precise, movement based editing and a careful attention to continuity were formative on what might be called invisible editing that is so ubiquitous as to be unnoticed in contemporary film making. The book too constructs scenes seamlessly, cutting away at the high points of action and allows each chapter to function almost as a short story or a scene in a screenplay. Perspective and point of view is important here too. Take the scene/chapter at the Hollywood party – it’s written like a tracking shot, following someone through the party as we pick up fragments of conversation before settling in to give a reassuringly familiar set up for a conversation between the key characters with the some diverting action in the background to keep the audience engaged. Or, take the scene where Pabst has to visit two executive producers to pitch his new movie idea (there’s a running joke about him always being mistaken for Fritz Lang which made me laugh every time it comes up). The whole sequence fits right into a slightly screwball comedy movie from the 1950s and it’s clearly been written by someone with a deep knowledge of not just Pabst’s own time of cinema but the conventions of visual narrative storytelling generally.

This is what Marco Bellardi calls “the cinematic mode in fiction”, which is helped along with “present-tense narration, the montage in general, a ‘certain’ visual quality of the texts, the camera-eye narratorial situation, a ‘dry’ dialogue, and the use of specific cinematic techniques such as travelling, pans, and zooms.” However, as Brandon Taylor points out in a piece/craft talk on the much contested term, “cinematic fiction is simply selective pressure taken to extremity.” The gaps and aporias of the novel structure are reflective of Pabst’s own inability to say the unsayable, to look beyond the structures of gesture and voice that make up his own work and confront the terrifying interrelatedness of his art and his quiescent complicity with the forces that put art to use.

Gretchen Felker-Martin’s Black Flame is also a novel concerned with the role and function of film – but whereas The Director is a novel of complicity and the great soothing corrupting lie of a-political cinema, Black Flame is a novel about desire, voyeurism and violence. To put things another way, The Director is about film making, Black Flame is about film watching.

The story follows Ellen, a pathologically repressed lesbian in her thirties living in New York and working as a film restorationist. Her bosses are casually anti-Semetic and so after landing themselves in some hot water with their work on restoring an old Klan movie, they agree to take on a long-thought-lost film from the 1940s called The Baroness made by Karla Bartok, a director killed by the Nazi’s for the double crime of being both Jewish and queer. The film, or rather film(s) are a potent melange of occult ritual, erotic transgression, sex and violence and it soon starts to get under Ellen’s skin — in one memorable scene quite literally — as it unlocks long repressed fantasies and desires. It leads to a spectacular grand-guignol conclusion in which the film tears through reality itself.

If The Director is cinema as historical fiction, then Black Flame‘s flavour of cinema is grindhouse punk. It is joyfully, shamelessly referential, a kinky pastiche of horror touchpoints that are both reassuringly familiar and shockingly alienating. There’s absolutely nothing wrong with this of course – the joy of genre is reading along to see how someone takes the familiar and twists things in new directions. For all the attention that the splattery details of Felker-Martin’s writing gets, (as Elizabeth Sandifer puts it, there are precious few writers as skilled at describing wet things) really what’s most interesting to me about the book is the interiority of Ellen’s character. She exists in a world which utterly hates her, but not nearly as much as she hates herself. The cursed object of the book isn’t so much the film but rather the closet in which pre-emptive self-loathing curdles into something that doesn’t just seek the repression of subjectivity but it’s complete annihilation.

A question is posed to Ellen throughout the book (and, by proxy to us as readers too) – “do you want it?” What is it that Ellen wants? They don’t necessarily know, or rather, can’t admit to herself the nature of her own desires. She is utterly repulsed by the sex and strangeness of the film at first, yet it makes its way into her dreams. Do we know what we want? A powerful point about cinema is that often we don’t know what we want – our desires, indeed our very sense of self and what a self is, are taught to us through cultural mediation. Ellen’s dreams of being somehow radically made other, of being inducted into relationships of pain, submission and freedom are, at first, inchoate, but by the time the book reaches it’s spectacular conclusion they are literally inscribed into her new flesh. Ellen’s dreams of being somehow radically made other, of being inducted into relationships of pain, submission and freedom are, at first, inchoate, but by the time the book reaches it’s spectacular conclusion they are literally inscribed into her new flesh.

Here, the structural corollary with cinema isn’t in the technicalities of the book’s production and structure but in its understanding of cinema’s perversity. This is Zizek’s point about film, right? “Cinema is the ultimate pervert art. It doesn’t give you what you desire – it tells you how to desire.” Desire is always structured through lack – the object of desire always just out of reach, on the other side of the screen. The other element worth bringing up here is the way in which the book understands this mediation and policing of desire to be unequivocally political. The appeal of fascist politics is in the libidinal thrill of sadism justified — look at the right-wing now (or the 80s throwbacks that populate the final pages of Black Flame) Are they happy? No, happiness doesn’t necessarily have anything to do with desire, instead all these people are thrilled – there is a libidinal economy of desire at work. This was Ernst Bloch’s point in Heritage of Our Time – the appeal of fascism was a swindle of revolution inasmuch as it didn’t promise you a better life, it made promises on the level of imagination. It didn’t speak to what you needed – it spoke to what you desired. There is a direct line between Riefenstahl’s propaganda films and the violent anti-Semetic heteropatriarchal queerphobia that structures Ellen’s lifeworld.

Does desire set you free? As Deleuze and Guattari write in Anti-Oedipus, “no society can tolerate a position of real desire without its structures of exploitation, servitude, and hierarchy being compromised.” Desire is about the formation of a new kind of subjectivity, but to become a new kind of person means the creation of a new world — even if the old must be burned down to ash to bring that into being.