Putting Vivarium into this series is maybe a slightly left field choice but I think it makes for a fascinating haunted house movie precisely because it cuts against so many of the generic expectations of what a haunted house story should be. Traditionally, the haunted house was about the intrusion of a long-thought-buried history, reintroducing itself back into a present which has forgotten it.

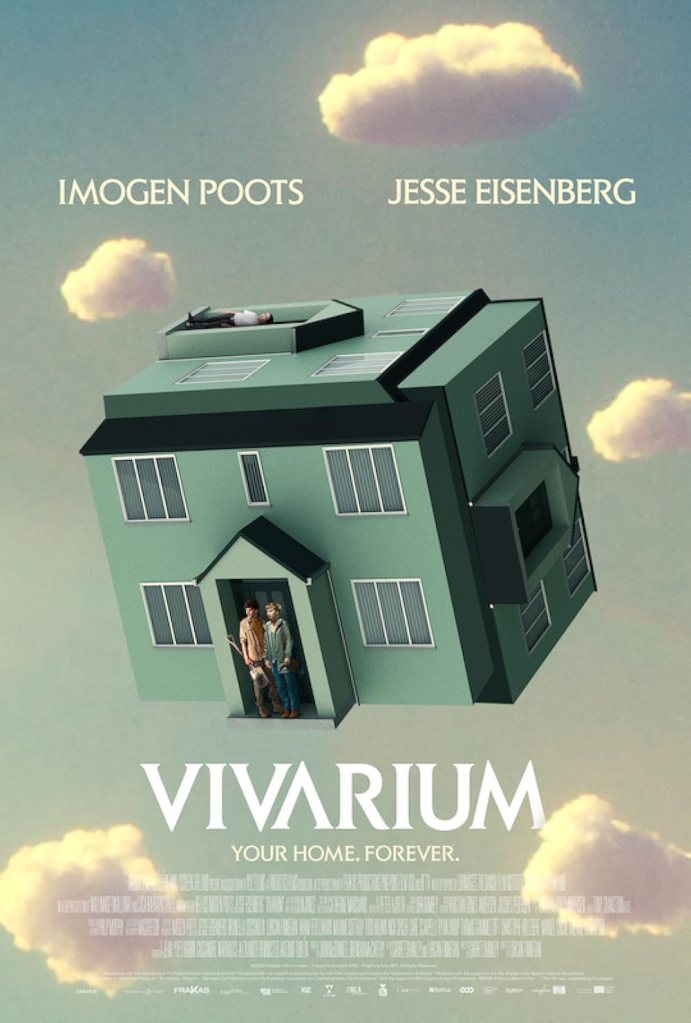

In contrast, Vivarium is about the place without history – suburbia – and the degree to which capitalist ahistoricity is both policed and naturalised. The film follows primary school teacher Gemma (Imogen Poots) and gardener Tom (Jesse Eisenberg) who are looking for their first home. After a strange meeting with Martin, a realtor who is perhaps a little too interested in whether the couple have children, they are shown to an estate called “Yonder” full of identical houses. Martin vanishes. The two, relieved and somewhat creeped out by the real estate agent, try to leave but every seemingly endless road brings them back to the home. There are no other people visible — Tom even burns down the house and the next day it’s restored. They end up having to stay, and then a child turns up on the doorstep along with a note telling them that if they raise the child, they will be released.

The child goes through accelerated growth and it becomes clear he isn’t quite human, staying up to watch strange fractal broadcasts on the TV. Driven by some obsessive impulse, Tom starts to dig a hole in the garden, eventually choosing to sleep out there before growing sick and eventually dying — what the child calls “being released”. He is placed inside a plastic bag and buried in the hole he had dug for himself. The estate, it turns out, is built on the bodies of the dead. Soon, Grace too will die, zipped into another one of those plastic bags, and the now full grown creature goes to work in a real estate office to start the entire cycle over again. The whole promise of suburbia is that it is the place outside time – the suburbs is the place with no history, with no ghosts. This might initially represent a problem — with no sense of history what space is there for the ghost but there are so many horror films devoted to proving that behind the facade, everything is built on death – the stand out example of this is absolutely something like Poltergeist or even something like Beetlejuice. Alternatively, the other side of suburbia in horror is that it is a void – a no-place, riven by some ontological evil (Carpenter’s Halloween and so much of David Lynch’s work both understand this in their own ways).

Interestingly, Vivarium works on both levels. The estate in which the two are imprisoned has no history and neither the estate nor anything in it is real — dig into the earth and all you’ll find is plastic once you go down far enough. In essence the film functions as a horror story about the naturalization of a specific configuration for social reproduction under capitalism. The very opening of the film shows a cuckoo in the nest – the outsider who appears to take up the resources and care of the mother and father, and who will throw their “true” offspring out of the nest to make room for itself. So it unfolds for Grace and Tom: they need a house, and so end up in suburbia mostly because that seems like what you are supposed to do. Grace is interestingly ambivalent about the idea of having children, but a child just appears, delivered as if by stork, or magic. The horror of suburbia which can be individualised in a morass of paranoia and surveillance is here universalised. Get out? Where to? Everything is the same. Besides, why would you want to go outside when food is delivered for you? Just this month the Telegraph were reporting that Britain’s were increasingly “voluntarily housebound” – driven by a combination of the slow erosion of third spaces, anxiety around the messiness and risk of social interaction and the ever expanding convenience of delivery.

This process of naturalization is why I’m a little skeptical about claims this is an eco-gothic film. The use of nature footage, and references to natural behaviour contrasted with the surreal and constructed environment serve only to underscore how artificial that which is taken to be “natural” really is. The whole bleak joke at the film’s heart is that none of this is natural – the suburbs are a vivarium, a constructed environment in which the only way out is death. All of the naturalised steps of capitalist social reproduction are highlighted as horrifyingly alienated, conducted as some bizarre experiment through which a non-human force seeks to perpetuate itself.

Strikingly, Tom and Grace have no chance of grasping what that force is – the alien creatures remain totally inscrutable to them – not only is the world in which they are trapped not natural, it can’t even be understood as properly political either. As I watched the film this time around, there was something I noticed that hadn’t struck me before. They don’t pay for the house. Price is never discussed. Getting on the housing ladder seems like a good idea — again, it’s one of those things which you are supposed to do, it is only natural to want a place of one’s own, but the actual transaction remains occluded and hidden away. Of course, that is partly because it isn’t necessary — after all, the true cost is their lives, but perhaps the other aspect is that recognising the home as a site of purchase makes it something less than natural, rendering the occultic force by which use value is transformed into exchange value more visible. Ultimately, the film makes me thing of what Mark Fisher wrote, that: “emancipatory politics must always destroy the appearance of a ‘natural order’, must reveal what is presented as necessary and inevitable to be a mere contingency.” That in essence is the true horror of the film, nothing has to be like this, but right now, we can’t find any way out.

One thought on “The Haunted House on Film Part Five”